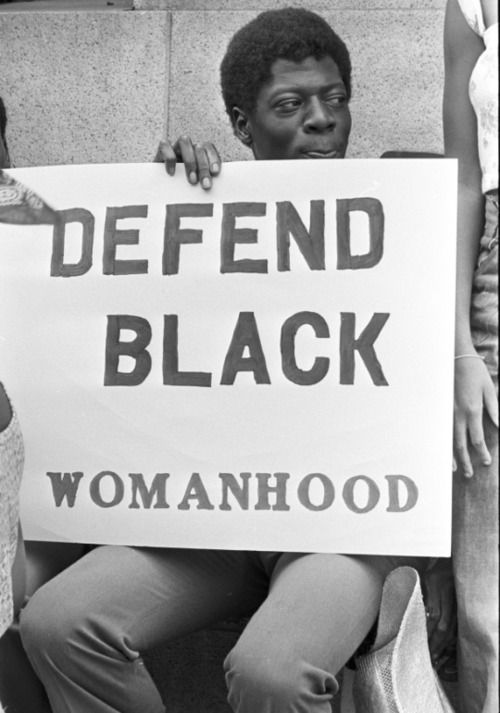

The life of a Black woman is one of constant expectation—forced maturity, unwavering responsibility, and emotional resilience demanded by society without consent. This phenomenon, known as adultification, strips Black girls of their right to childhood, forcing them into roles of discipline and strength before they’re ready. The effects of this bias extend beyond adolescence, shaping their experiences from grade school to graduate programs.

Black girls are disproportionately disciplined in schools, their vulnerability erased and their right to softness denied. But what happens when they enter spaces created for their empowerment? Even at Spelman College—a place built to nurture and uplift Black women—does adultification still persist? And if so, how does it manifest in a community built for us, by us?

Childhood should be a time for innocence, exploration, and guided growth. But for Black children—especially Black girls—innocence is a luxury society often refuses to grant.

Historically, this denial of childhood dates back to enslavement. As noted in historical accounts, “Black girls were imagined as chattel and were often put to work as young as two and three years old. Subjected to much of the same dehumanization suffered by Black adults, Black children were rarely perceived as being worthy of playtime and severely punished for exhibiting normal child-like behaviors.” What once looked like a lack of toys or playtime has evolved into disciplinary action for natural human development—like puberty.

Adultification bias doesn’t end with dress code policing. It extends to harsher discipline and unrealistic expectations placed on Black girls for perceived infractions—being “disruptive,” “defiant,” or “inappropriate.” Often, these perceptions are shaped by tone, body language, or physical development.

In classrooms, this results in unequal punishment. White students may be pulled aside for a conversation. Black girls face suspensions, expulsions, and, in some cases, early encounters with law enforcement. Meanwhile, they’re expected to exhibit more emotional restraint, maturity, and responsibility than their peers.

But these biases don’t fade as Black girls grow up—they evolve. And they follow students into institutions designed to serve them.

Spelman College, founded to educate Black women excluded from predominantly white institutions, was established as a refuge—a space to foster personal and intellectual growth. Here, Black women were the majority. Here, they could be celebrated in all their complexity. But over time, adultification bias has seeped in, reshaping how vulnerability, excellence, and worth are perceived—even within this sanctuary.

What was meant to shield Black women from societal harm now sometimes mirrors the same pressures. The expectation to be “the best” has become a standard. At Spelman, excellence is not just encouraged but demanded. And too often, that pursuit of excellence comes at the cost of softness and self-exploration.

For first-year students, integration into Spelman’s community often starts with joining a registered student organization. This process can feel overwhelming for those without prior access to mentorship or support.

“At Spelman, women are often measured by the number of their accomplishments rather than their quality,” said Mallory Childs, a first-year sociology major. While Spelman’s competitive culture prepares students for the outside world, Childs noted, it also “reinforces the idea that Black women must always be exceptional to be seen as worthy.”

In a space meant to uplift, the pressure to be perfect can leave little room for failure, mistakes, or vulnerability.

“The challenge,” Childs added, “is to be accepted as human first rather than just a list of achievements.”

Sonah Bundu, the 1st Attendant to Miss Maroon & White and a graduating senior at Spelman, echoed that sentiment. As founder of The Spelman Society of Cosmetic Scientists, Bundu said leadership comes with intense pressure.

“Spelman College expects students to compete with themselves… Spelman took a boss from every school and put them in one place,” said Bundu.

That competitiveness shapes everything, including how students present themselves. Even in informal settings like the dining hall, she noted, wearing a bonnet can draw criticism from faculty who expect students to always appear “put together.”

“The image of a Spelman Woman and adultification goes hand in hand… young women are expected to look presentable at all times, at Spelman there is the same expectation,” Bundu said.

Spelman’s culture, she explained, offers little room for softness. “Spelman is a ‘dog eat dog world’ where rejection is met with ‘wipe your tears and try again’ rather than comfort.”

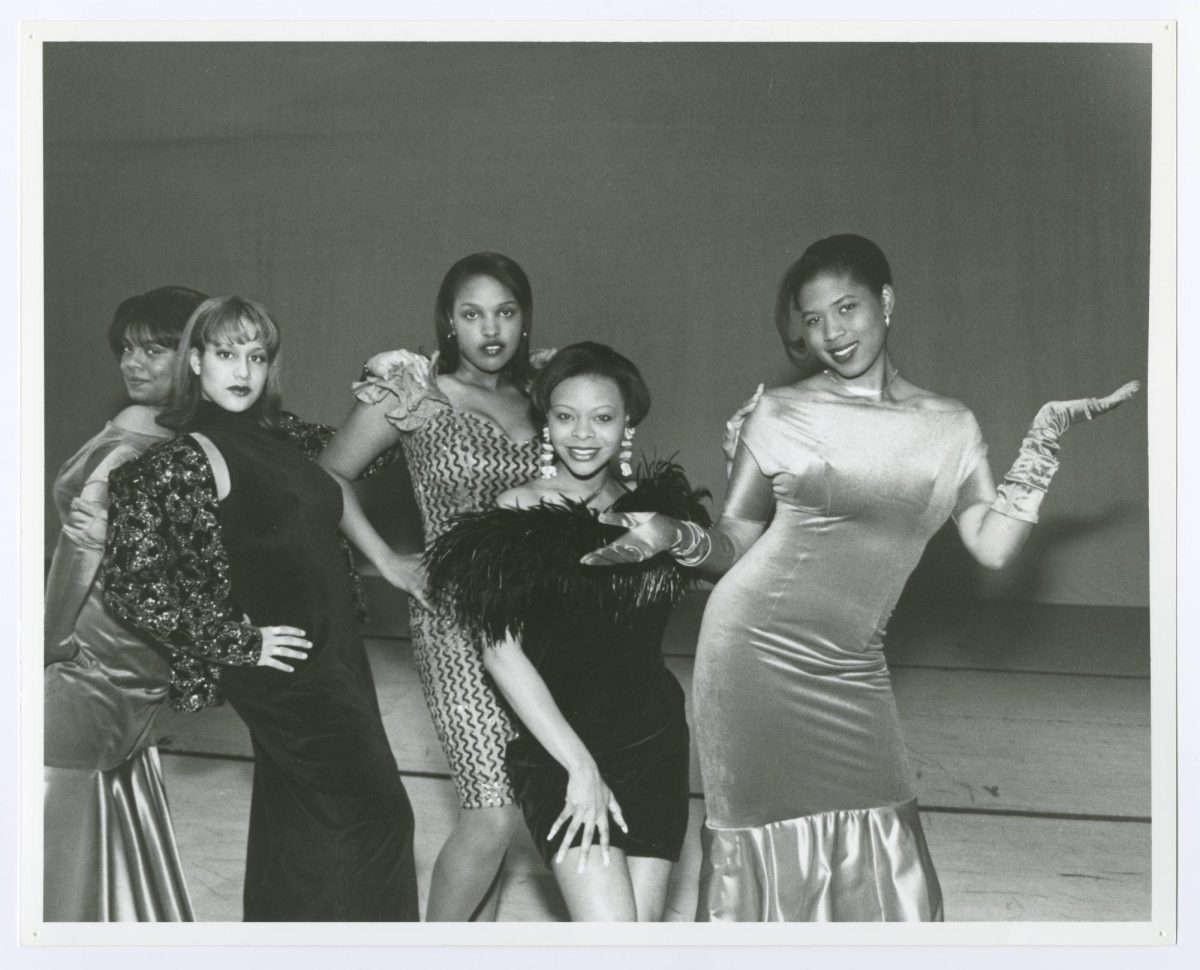

Even in traditionally celebrated roles like HBCU queenship, Bundu felt the pressure to conform to a more traditional image—one that left no room for personal expression.

“There is no space for vulnerability,” she said, explaining how she felt the need to downplay her piercings and henna to align with expectations of what a queen should look like.

While Spelman fosters academic excellence, it often reinforces the expectation that Black women must always remain polished, strong, and self-sufficient.

Chaundra Lewis, Henry State Court Judge and Spelman alumna (‘95), acknowledged this duality. “Spelman does an exceptional job of uplifting Black women,” she said, particularly by reminding them of their historical strength. But she also noted the downside: “We must always have it together” to prove our worth.

That pressure, she said, doesn’t begin in college, it begins at home.

“Black mothers, grandmothers, and aunts commonly teach young Black girls to take on adult responsibilities, such as cooking, cleaning, and caring for younger siblings,” Lewis said.

In professional settings, those expectations only continue. “As a Black woman in a leadership position, her authority is often questioned, and decisions challenged, and the expectation is that I have not earned a seat at the table—until I show them otherwise,” Lewis added.

Pearl Coleman, a Georgia native and current Spelman Ambassador, agreed that adultification remains present at Spelman and other HBCUs. “Specifically here at Spelman, I feel the culture expects us to be strong women straight out of high school—smart women who are able to handle everything handed to them at once, and caretaker to the young men across the street at the same time,” Coleman said.

While the Spelman Woman ideal is often empowering, Coleman said it can also be limiting—especially when that ideal expects perfection from an 18-year-old.

Spelman does an exceptional job of preparing its women for the future, equipping them with confidence, intellect, and resilience needed to navigate a world that often underestimates them. However, this preparation sometimes comes at the expense of the student’ personal feelings, reinforcing the notion that emotional expression and vulnerability are secondary to success.

While the institution prides itself in producing trailblazers, the pressures to constantly perform, achieve, and uphold the Spelman Woman ideal can leave little room for students to process their struggles without being fearful of being perceived as weak.

The ongoing adultification prejudice, even inside Spelman College, exposes a larger issue: how can schools meant for Black women to promote success without adding the same constraints they try to destroy? The demand of unrelenting strength and perfection excludes much space for tenderness, sensitivity, and self-discovery. If Spelman wants to be a refuge for Black women, it has to understand that empowerment also involves making space for flaws. Growth should not come at the expense of humanity; worthiness should not depend just on endurance.

Ultimately, breaking the cycle of adultification requires a cultural shift–one acknowledges Black women’s right to be multifaceted individuals rather than symbols of strength and perseverance.

Institutions like Spelman College should work to create spaces where Black women can genuinely express their identities, participate in joy, rest, and discovery free from the burden of judgement. Spelman may lead by example, showing that Black women are deserving of the freedom to genuinely live by challenging the traditional measures of achievement linked to suffering.

Bennette Davis • Apr 16, 2025 at 8:16 am

Beautiful say!

Chitina Fulford • Apr 15, 2025 at 1:22 pm

Hi Charity,

I just finished reading the article you shared on Black women and adultification, and I have to say—it’s absolutely excellent. It’s so well written and offers such a powerful, clear understanding of an issue that’s far too often overlooked or misunderstood. The way it breaks down the historical context and emotional impact really resonated with me. Thank you for sharing something so necessary and insightful. I truly appreciate it.

Phyllis D Teel • Apr 18, 2025 at 9:12 pm

Hi Charity,

Your paper is awesome! You touched on all aspects of being a strong intellectual black woman. It resonated with me as a black female soldier out of high school; also pursued higher education during my entire military career, and encountered so many basis from black males, white males, and white women. Fighting for my country at age 18, yet still maturing to become a woman. We adapt, adjust, and achieve with greatness! Charity, you have always been an exceptional black female with a strong black mother . Your mother being the leader that she is invested in you, and ensured that you’re among the best! Charity you the best…..just remember you are loved!