As of my writing this, I have no plans to vote in the 2024 Presidential Election. I have not voted in any prior elections since turning 18, and I have no intention to vote in any future presidential elections.

This is a stance that, when publicized, has earned me much judgment from my peers, professors, and family members alike. The justifications, shaming, pressuring, and social outcasting that occur in an attempt to encourage others to vote are endless. This is especially burdensome when attending an institution such as Spelman, where neo-liberalist attitudes (ironically; see here for context) run abundant.

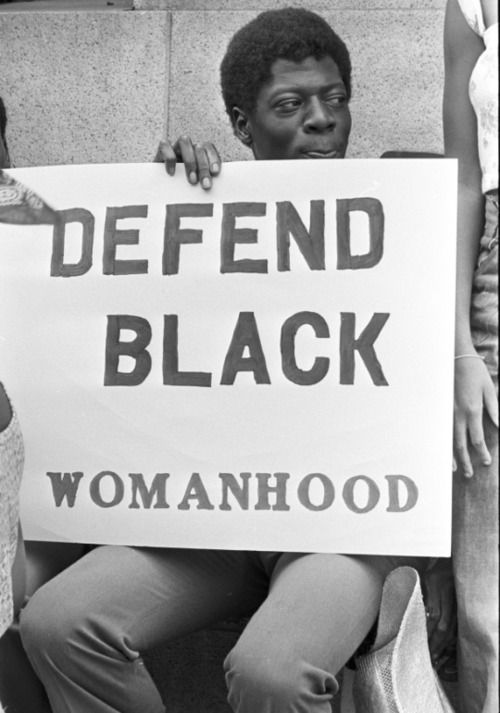

I want to spend some time today addressing and debunking some of the major arguments that are used to shepherd others into voting. The one that I hear most often, usually aimed at or by Black people to other Black people, is that my ancestors died for me to vote, and therefore to not utilize my right to vote is to disrespect the legacy of those who are directly responsible for my existence on this planet. This plea relies on notions of heroic sacrifice in order to guilt the receiver into feeling obligated to vote. I find this to be one of the most abhorrent and frankly nonsensical out of the commonly used arguments in favor of voting, because it uses death in a casually manipulative way that serves the agenda of the corrupt American governmental apparatus.

First of all, this statement becomes easy to poke holes in if you first just recognize that logically, all of our ancestors would not have died for us to vote. When I think of the AUC and its current community of politically engaged individuals — used in this sense to mean individuals who have thoughts and opinions about our current political climate — it goes without saying that it’s made up of people who have vastly different opinions in regards to how we should proceed in our world. Given this, would it be so impossible to imagine our ancestors in the same way, as people with vastly different views, some of whom wouldn’t have supported voting?

Not only is this not impossible to imagine, but it’s also irresponsible not to, because it presents our ancestors as monolithic and flattens the other, varied goals of the civil rights movement in order to hyperfocus on the one issue of suffrage. It seems more fair to say that our ancestors who put their lives on the line in the civil rights movement did so for the larger goal of liberation. And while some may have seen voting as a means to this, others certainly didn’t.

Proof of such divergence in political thought becomes no clearer than in reading W.E.B DuBois’ 1956 article aptly titled, “I Won’t Vote,” or Lucy Parsons’ 1905 “The Ballot Humbug”. It’s almost eerie how much of their criticisms and observations of American politics ring true today, especially as DuBois says, “I believe that democracy has so far disappeared in the United States that no ‘two evils’ exist. There is but one evil party with two names, and it will be elected despite all I can do or say. There is no third party.”

I want to focus more on DuBois here because he is a heralded figure within the AUC, particularly at Morehouse and Spelman, where at the former he is the namesake of a freshman dorm and at the latter, we’re assigned to read much of his works in our required freshman African Diaspora and The World class. So when some of the same people who idolize our radical “ancestors” then go on to espouse that they died for us to vote, they are simply being uninformed of the ancestors whom they speak of.

I have no way of knowing if my specific ancestors believed in voting or not. But either way, even if they did believe in voting, I don’t feel any obligation to mirror their political views on the virtue of them being my ancestors. My ancestors, like me, were human beings who were imperfect and whose views were informed by their experiences, which may have been limited in some ways. Whose to say that their views weren’t flexible and could have changed had they been educated differently? Furthermore, I can say currently that I don’t agree with a majority of my family members’ political views, even though their sacrifices on my behalf are readily visible to me.

I’m also uncomfortable with the way we invoke “the ancestors” as this sort of all-knowing, infallible, unquestionable thing, because again, it robs what were actually millions of individuals of their human-ness, their imperfect-ness, their likely occasional wrong-ness, and puts them on this strange, fetishistic pedestal.

Though I could stop here, I want to briefly touch on three other commonly used arguments used to encourage others to vote. First is the idea of this election — like many of its predecessors – being a “fight for our democracy.” Such statements are typically used in tandem with others that seek to create a similar sense of fatal urgency — claims that this is the most important election of our lives, that things have never been more critical than they are now, that everyone’s basic human rights are on the ballot.

Simply thinking about the fact that I am still here, alive, writing this article despite exaggerated claims of my human rights being on the ballot every election since I was a child, it’s only natural for me to put little belief in them. And that’s not to say that I don’t experience systemic barriers or that my life isn’t severely limited because of my class and identity, but rather that this status hasn’t changed regardless of who’s been in office.

Anyway, I want to turn my focus mainly towards the idea of elections being mud fights for the mythologized “democracy,” a form of government that has simply never existed in the United States.

To be clear, the Merriam-Webster dictionary describes democracy as, “a government in which the supreme power is vested in the people and exercised by them directly or indirectly through a system of representation usually involving periodically held free elections.” We know already that there was a time in which Black people did not have the ability to exercise this so-called power that is inherent to democracy. Even today, while we tout that the right to vote has been won, voter disenfranchisement runs rampant throughout our country, evident in practices such as voter roll purges and the fact that felons are denied the right to vote.

Putting race aside, no member of our society — white, Black, or otherwise – can say that they possess this so-called “supreme power,” when our vote still leaves us helpless in matters such as abortion and affirmative action strike-downs, among other examples. So what are we fighting to sustain, really? The right to continue to be powerless?

Next, I want to turn my attention to the statement that they (“they” being this generalized, unnamed, scary, oppressive force) wouldn’t be working so hard to take away our right to vote if it wasn’t important. And while, true, I’ve acknowledged in my last paragraph all the ways in which our vote has historically and continuously been suppressed, this fact – if anything – gives me more reason not to vote. The clear unfairness of the system makes me believe that we need to create a new system and stop participating in this one. As a student, if I don’t like a particular section of a class, I’ll move to a different one. If enough people move to that new section, then the previous, unsatisfactory one, will cease to exist.

And while I’ve heard from some people that this is the attitude of a quitter, of a person who gives up in the face of adversity, to that I explain that not voting only inspires me to find other ways to contribute to the betterment of community, ways that are more direct and immediate than a vote could ever be. So the powers that be don’t want me to vote? I won’t continue barking up a tree that was built for me to fall with each attempt, when I can simply walk around it.

I’ll end this article by addressing a final sentiment that I often receive in response to my non-voting stance: there is no harm in voting, so why not do it if it’s at no cost to me? This argument is reminiscent of the philosophical Pascal’s Wager – the idea that one should believe in God because they stand only to gain if he indeed exists, and lose exponentially by not doing so. To this, I’ll say that my moral consciousness is of great personal importance to me. To vote would be to cast aside the values that make me the human being I am today.

Not only am I morally opposed to both candidates in this election, but I’m morally opposed to the idea of a president in general — meaning, there is nothing either candidate can do, nor any future candidate (unicorn or otherwise) to earn my vote. So, until our society can make a commitment to destroying the system as we know it entirely, I will continue to respond to the above justifications with eye-rolls and disdain.

Rokiyah Darbo • Sep 24, 2024 at 10:53 pm

Thank you for this.

Zakai Jaleel (Ex Morehouse) • Sep 22, 2024 at 9:05 pm

She one of dem ones. This opinion piece is through and I expected nothing less from the number one writer. Not afraid to go against the grain which is what the auc is about. Yall all deserve yall flowers but please give her the whole garden✨