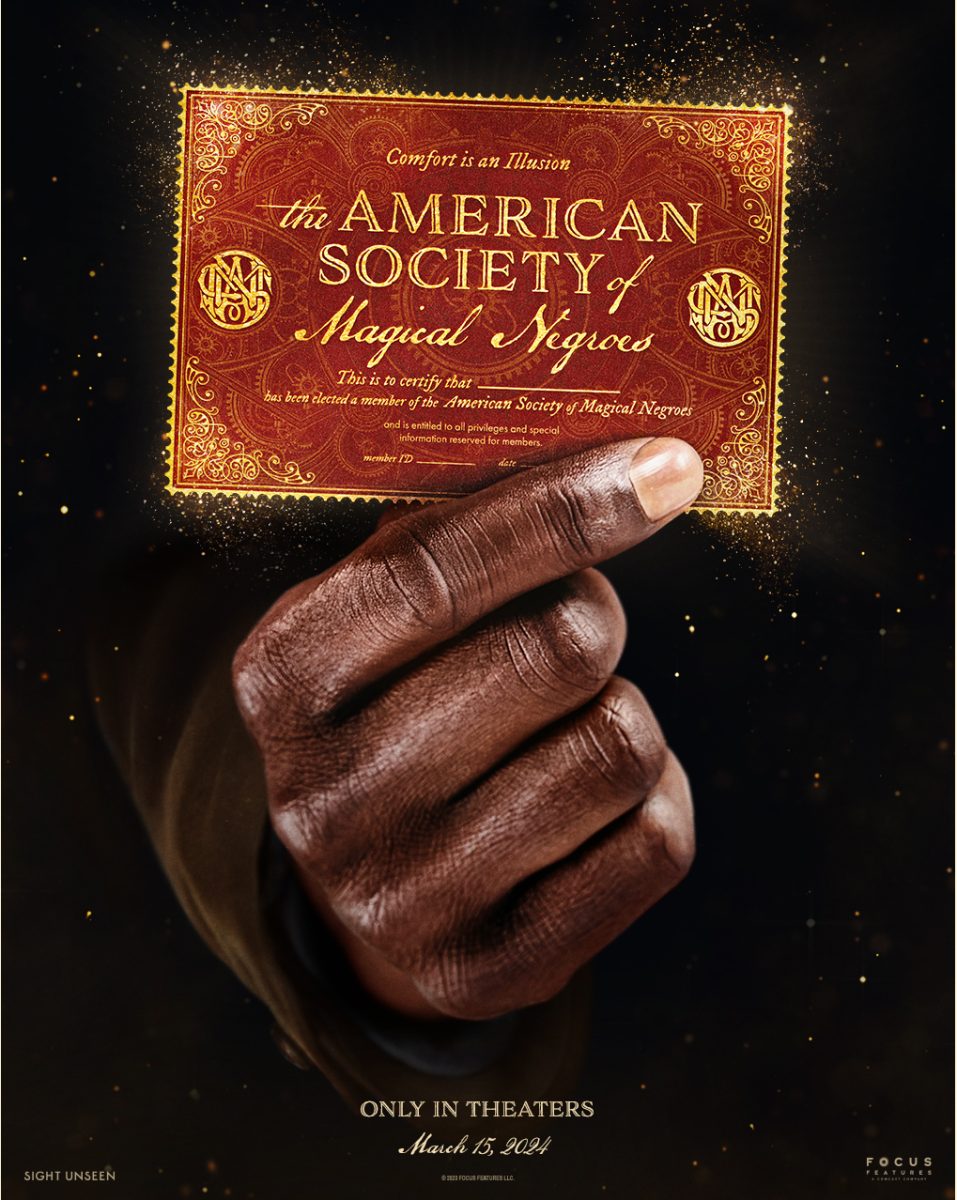

As the new year rolled in, whether halted by the SAG-AFTRA writers’ and actors’ strikes or simply already on the docket for 2024 release dates, many movie trailers and original films have been hitting the big screens. Among these movie trailers was one that dazzled everyone’s screens with sparks of mysticism, marvels, and magic. With a primarily Black cast starring Justice Smith, David Alan Grier, and Nicole Byer, some ran to the box office ready to encounter a wizarding world of a Black version of the Harry Potter franchise. Watching the trailer of The American Society of Magical Negroes, in its entirety and sitting down as the opening scene began to roll, it was affirmed that this was indeed not a “Black Harry Potter,” but rather a contemporary satire and magical realist tale of a devastating reality. Watching the movie in theaters as two young American Black women, we found ourselves not only cringing with second-hand embarrassment from Aren’s relatable experience but also from the very few Black female characters portrayed in the movie. While this magical tale is a modern truth for many Black Americans, whose Black reality is authentically represented? Does this impact those who aren’t?

Kobi Libii’s debut film, The American Society of Magical Negroes depicts the universal Black American experience of social unease when attempting to make white people feel comfortable in social, professional, and personal situations and aid in their triumphs in hopes of protecting themselves from racial harm. Nevertheless, Aren’s personal discoveries throughout the process of working for the secret Black society, the movie proves evident that, as Justice Smith stated in our interview, “palatability won’t save you.” One’s conformity and alteration of their identity and character for another’s gain provides a life of isolation, self-deprecation, loss of self, and ultimate self-destruction. Witnessing Aren’s passive behavior slowly became unbearable, but it was an affair we knew all too well. Much like the majority of Black people in America, we find ourselves acting as the “supporting character” to a white counterpart’s plot. However, the job of The American Society of Magical Negroes to support white people’s needs has historically been the burden of Black women and their perceived “Black Girl Magic” in America for centuries. What is the “magic” of being a Black girl in American society? Is it our unwavering power to do anything we put our minds to, or being extraordinary in both the white and Black male gaze and in conforming to white society to make their white counterparts and Black men comfortable with ease? After sitting down for a roundtable interview with the movie’s writer and director, Kobi Libii, and star, Justice Smith, last Tues., March 5th, we discussed the movie’s purpose, what Libii intended to convey, and what audiences received.

Libii explains in our interview that the movie is not meant to tell the story of all Black American experiences. It tells the story of Black people in American society whose simple ability to survive racial adversity and hatred makes them the heroes of this battle, reassuring the non-rebellious that’s meant to be what he describes as “thought-provoking.” However, this story excludes and misrepresents any form of Black woman’s role in this heroism. While Blackness is non-monolithic, making it arguably impossible to depict the identity and experience of all Black people in America, excluding Black women, the intrinsic member of the Black family, community, and overall society who is uniquely impacted by this issue, further harms Black women and the notions surrounding them. Rather than conveying an equally well-developed and authentic Black female character, the movie perpetuates common stereotypes, archetypes, and tropes of the Black woman.

Nicole Byer, a comedian and Netflix baking competition host of Nailed It and what Kobi describes her as charismatic, was cast as the American Society of Magical Negroes’ leader, DeDe. DeDe’s authoritative position as the backbone of a community of select Black members of American society acts as the chief upholder of subservience to white society. DeDe’s unwavering loyalty illustrates the “Mammy” caricature and stereotype, one of the many negative stereotypes used to depict Black women.

The Mammy stereotype was born from slavery and through the Jim Crow era; during slavery, the Mammy caricature stood as an example that Black people, particularly Black women, were content, even happy being enslaved, though they were undoubtedly far from it. DeDe’s character in the movie does seem happy with her situation. DeDe stands as the epitome of contentment and joy with her position as a servant to white people’s emotions and aspirations.

DeDe is more than happy to do her job as a servant to white people’s needs as, parallel to the Mammy caricature; she visibly wears vibrant colors like the vibrant reds of the Mammy picture’s costume. She laughs and smiles with joy as she buoyantly floats above her followers.

DeDe, along with the only other Black female “representation” presented, Gabbard, played by True Blood’s Aisha Hinds, who teaches the members how to use their magic to fulfill their roles, is often compelling their fellow Black society members to treat their white “clients” with almost motherly warmth and compassion to inspire White people to achieve more in their lives. However, when interacting with other Black people, DeDe yells at, shames, and scorns those who fight for autonomy and liberation from their docile positions.

Ultimately, we don’t know much about DeDe’s character other than the fact that she is vivacious and excited to fight the “cause” of making white people feel comfortable and shielded from what Robin DiAngelo calls white fragility, the discomfort, and defensiveness a white individual feels when confronted with information regarding racial inequality and injustice. With limited information for the depth of DeDe’s identity, her character in the movie is incomplete or is “half-baked,” to which Nicole would cheerfully say, “Nailed it!” as she does on her hit Netflix show, Nailed It, when a cake in fact did not “nail it.”

Why did DeDe decide to lead the American Society of Magical Negroes? Where is she from? What is her background? What aspects of her life fueled her beliefs? While this Mammy illustration may be the satire of it all, is it a positive representation of Black womanhood that film and television consistently lack? We don’t particularly find this so.

Kobi’s movie is powerful in its ability to open conversations regarding racial discourse and Black strife in America; however, Black women are excluded from this conversation as they have been for centuries. Historically, Black women have been vital to the labor movement for Black freedom and justice. While Aren’s image of the soft and gentle Black man, or what Kobi and Justice call “a gentle straight,” fights the “strong Black man” stereotype, the intersectionality of a Black woman fighting the subservient stereotypes of the Mammy and the “angry Black woman” stereotypes while being the “Black girl magic” archetype is not portrayed. Where do Black women fit within this “wizarding world” of the American Society of Magical Negores? Being a supporting character for both Black men and her White counterparts, do Black women have a more complete character in the universe of Kobi’s movie, or do they need their own American Society of Magical Negroes?

Additionally, this film made an effort to touch on notions of Black survival, specifically with the conversation between characters Aren and Roger. Roger mentions that survival within the Black community is an act of resistance. While we do not wholly disagree, the film could have made a more conscious effort to interrogate other modes of resistance prominent in the Black community, like the prevalence of Black Death. Historically, members of the Black community have viewed death as a valid form of resistance because they would rather die than be a part of a system that actively negated their humanity. Through this film, we would have liked to understand what it means to survive in a country consumed by anti-Blackness. Does survival look like complacency, or is it total disruption? Although, even through the lens of Black survival, Libii again “forgot” to recognize Black women. It is no surprise that Black women sit at the center of the Black community and have had roles dedicated to Black survival since times of enslavement. This is thoughtfully articulated in Angela Davis’ piece Reflections on the Black Woman’s Role in the Community of Slaves on JSTOR where she says,

“As the center of domestic life, the only life at all removed from the arena of exploitation, and thus as an important source of survival, the Black woman could play a pivotal role in nurturing the thrust towards freedom.” Therefore, Black survival does not exist without Black women’s robust influence and support.

Furthermore, a particular line stuck out in Aren’s validated outburst against his co-worker Jason: “This country is deeply indifferent to the fact that I exist.” While we empathize with the frustration that Aren was feeling at that moment, this statement is not necessarily accurate; instead, it actually ignores what it means to be a Black person living in the United States. Now, of course, we recognize that the Black experience is not a monolith; however, the construction of Blackness is the entire reason that this country exists. To be Black is to have everything predicated on your exclusion.

Black Feminist scholar Hortense Spillers says it best in her piece Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book on JSTOR, where she asserts, “My country needs me, and if I were not here, I would have to be invented.” So no, we don’t agree that America is indifferent to the existence of Black folks, but instead, our existence is mandated to continue to produce white supremacist realities.

The Black experience is like living in constant oscillation between negrophilia (fetishization) and Negrophobia (anti-Blackness), and this film completely missed the mark in its depth, as it did not even begin to scratch the surface of what it means to be Black in a country like the United States. As described by Libii, this film was meant to tell his story and allow the Black audience to feel validated. Unfortunately, this film still adhered to the same respectability politics that Libii hoped to deconstruct.

We acknowledge that the film was a little under two hours and that a lot of the nuance we hoped for would be difficult to showcase. However, regardless of the length, a more conscious effort could have been made to create a film that didn’t contribute to the erasure and reduction of Black women. The intention behind Libii’s film was brave, but unfortunately, it missed the mark in producing something that was genuinely thought-provoking. Despite the holes in this film, we applaud Libii for his vision of imagining a magical Black society in a way that many of us have not seen before.