Homecoming. The one night a year when a student can trash campus and no one can say anything about it.

When I went tailgating for the first time last year, I thought I was being moshed against my will. Whether one entered the tailgate vicinity before or after the football game, it felt like the clashing of my body against another’s was an inescapable misfortune. Unbeknownst to me, if my arms were being grazed by water, one’s sweat, Fenty body butter, or a mixture of all three, I left the event scathed with overstimulation.

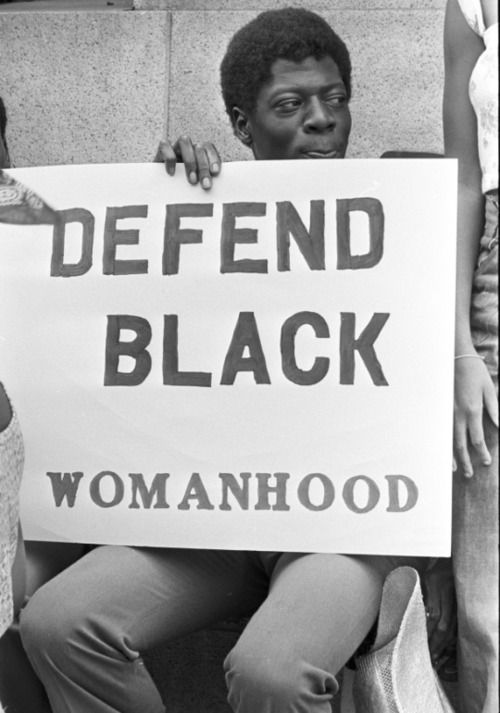

Once a mere street that I would idly cross when walking to Morehouse: during tailgate, it was suddenly plastered with bodies. Glistening melanin spanning as far as you can see, it was almost surreal to witness such a mass congregation of Black beings. Whether one was catching up with their former classmates, grabbing food from a friendly alumni, or desperately clasping onto their friend’s hand to maneuver through the crowd, tailgating is a memorable Homecoming staple for the Spelhouse community.

Whilst walking through the tailgate crowd, the odds of stepping on a littered can or someone’s foot are honestly equivalent. With Homecoming as a whole ranging to roughly 40,000 attendants annually, when compared with Spelman’s total undergraduate enrollment in 2023 — 2,588 students — the Homecoming population is 20 times that. Placed under an environmentalist perspective, if per day, an average American produces around 4.9 pounds of Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) (United States Environmental Protection Agency), when multiplied by 40,000 attendees, during the entire week of Homecoming, an estimated 196,000 pounds (98 tons) of waste are produced.

A mass quantity of such waste is generated during the Homecoming tailgate event, as alumni and students are scattered across campus hosting potlucks or day drinking with products that are on “Top 10 Most Littered Plastic Items in the U.S.” list. Largely because of their convenience and cheap cost, when tailgating, individuals often use plastics like expanded polystyrene to hold their food, plastic bags, plastic water bottles, and single-serve wine/liquor so that once done drinking or eating, they can easily dispose of their waste. With minimal trash cans readily accessible during the event (due to the implementation of scant large event management), such resources are overfilled fast, causing many attendees to litter as their next resort. Presented with the rationale that disposing of their singular plastic item “poses no environmental threats”, when placed in conjunction with how 40,000 individuals have the same logic, we are met with the aforementioned statistic of 196,000 pounds of waste being amassed throughout the week.

When one million plastic bottles are purchased every minute, up to five trillion plastic bags are used worldwide every year, and 400 million tonnes of plastic waste are produced annually (UN Environmental Programme), one’s singular act of littering subsequently accumulates into a larger environmental issue. “Plastic waste can take anywhere from 20 to 500 years to decompose, and even then, it never fully disappears; it just gets smaller and smaller” (United Nations). As a result, large gatherings like Homecoming pose the question of how individuals can engage in fun while being environmentally conscious beings.

Throughout the school year, when my friends and I are overwhelmed and/or want to decompress from the day, we engage in what we call “AUC walks,” where we walk around different parts of Spelman, Morehouse and Clark’s campus and debrief about what’s going on in our lives. Craving mental ease after tailgating and needing a space to self-tranquilize, when all the attendees had gone home from their day festivities and the AUC was predominantly vacant, my friends and I took one of those walks.

Not even five minutes in, upon entering Morehouse’s campus and passing in front of their bookstore, I physically stopped in my tracks, aghast at the sheer disarray their campus was in. Peering below their circular tables and walking down to see the street that spanned in front of the Martin Luther King Jr. International Chapel, virtually every crevice of concrete was littered with waste: aluminum cans, polystyrene containers, and even spodic instances of vomit. It looked like the purge or an orchestrated prank that Spelhouse fell victim to. Usually a tidy area, seeing their campus in that state was incredibly jarring, especially when one considered the people responsible for cleaning it up.

When the football game is over and tailgating has drawn to a close, everyone goes their separate ways, leaving behind overflowing trash bins and a trail of garbage for people to address in the morning before everyone wakes up. A group that has engaged in annual Homecoming cleanups since the pandemic is The Midnight Riot. Founded by Spelhouse alumni Charles Jackson and Kyarah Barton, the Midnight Riot is a coalition of artists, students, community members, and organizers dedicated to advancing efforts toward environmental equity and underscoring the intersections of environmentalism and social justice. As a non-profit organization based in Atlanta and Indianapolis, The Midnight Riot advocates for its initiatives through programs such as trash cleanups, educational workshops, and their Riot Cares initiative of collecting and donating resources to communities in need.

Having been a member of The Midnight Riot since freshman year, Kyarah and Charles humbly emphasized how they would never claim to be at the forefront of these clean-ups as, if they weren’t involved, “someone would’ve eventually done the work.” Collecting upwards of 45 bags of trash last year Post-tailgate, the organization annually engages in such work so individuals can not only be in spaces of environmental community and fellowship but also highlight the lack of care that the AUC community displays toward the larger West End community (The West End, Ashview Heights and Vine City)

Many students, alumni, and general attendants of Homecoming are unaware that their festivities impact the individuals around them, specifically areas that don’t have the infrastructure to adequately address the environmental strains large events like Homecoming pose. Specifically touching on how at the end of Homecoming, there are large amounts of trash in the streets, on sidewalks, and in greenspaces, the sheer amount of scattered environmental waste underscores not only the lack of care that both the City of Atlanta and broader AUC community display towards adjacent (marginalized) communities, but the urgent need for systems of environmental equity to address the disparities in waste management and recycling systems.

The prevalence of waste throughout Homecoming is exacerbated due to the wave of individuals that are coming to a very small location, creating a pressure point on the black communities HBCUs like Spelman and Morehouse are neighboring shared Darryl Haddock, Environmental Scientist and Special Projects Director at WAWA.

One large problem adjacent communities encounter post-festivities like Homecoming is storm drains clogged with waste. Such is because the discarded bottles and packaging littered on streets typically end up in them due to heavy winds and rain. Storm drains are essential for communities as they help prevent flooding and protect neighborhoods, streets, and curbs due to them collecting stormwater to divert rainwater from streets and other paved surfaces into bodies of water. Thus, when such infrastructures are choked with debris and waste from events like Homecoming and tailgating, environmental harm is posed onto local communities’ waterways and water systems, largely because they are then more susceptible to the risk of flooding and accompanying property damage.

The lack of designated cleanup efforts in these areas exacerbates the problem, as the neglect of local communities leaves their residents to contend with the remnants of the celebrations long after the festivities have concluded. Such experiences affect both the cleanliness of their streets and undermine the quality of life for the people living in these communities.

An overwhelming response to topics surrounding environmental injustice is, what can we do? Releasing an open letter to the AUC Institutions upon the publication of this article, The Midnight Riot outlined a few ways the AUC administration, and their respective students can amend the mentioned concerns surrounding the environmental ramifications of Homecoming activities.

A main point of contention was the need for the AUC to be more proactive rather than reactive when it comes to highly anticipated large campus events. Knowing that Homecoming is an eventual period for students, the AUC community can have large event waste management implemented beforehand so that attendees are able to have trash and recycling cans readily accessible to properly dispose of their waste.

When hosting such events, increased awareness, instruction, and strategies should also be prioritized so that attendees are aware of where and how to dispose of their waste responsibly rather than littering and throwing their trash on the ground. Preliminary actions like upcycling and reusing items for Homecoming can aid in this instance as attendees would be “extending the useful life of things, keeping them out of the landfill a little bit longer, and helping people adjacent communities,” comments Jonelle Dawkins, Executive Director at Scraplanta. Especially when considering how ephemeral consumerism is during Homecoming due to people buying cheap fast fashion clothing, and storing food in single-use containers, when attending these large events, individuals need to start asking themselves: “What can I reuse instead of dispose?” adds Dawkins.

Lastly, administrations on Spelman and Morehouse College’s campus simply listening to community members, student organizations, and nonprofits about their environmental concerns surrounding events like Homecoming is an effective first step. Learning from your community is incredibly fruitful, especially when considering that there are already people putting in the work to help who just need support and funding. Highlighting non-profit organizations like The Midnight Riot and Scraplanta, they are evidence that there are ways we can support the greater Atlanta community if we do things as a collective to alleviate the burdens such communities face.