On January 20th, 2025, Donald J. Trump was inaugurated as the 47th president of the United States. One of the most prominent issues of the 2024 election was immigration policy– during President Trump’s first presidential run, he became infamous for his strict views on limiting immigration, particularly from Mexico and other Latin American countries. A central promise of his 2016 campaign was building a wall along the US-Mexico border, and he has consistently used prejudiced, inflammatory rhetoric in describing Mexican immigrants. In a 2018 speech, he noted, “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best… They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.” That same year, his administration implemented a “Zero-Tolerance” deterrence policy that further enabled the separation of thousands of migrant families, many of whom still have not been reunited.

In examining the first few months of Trump’s second presidential term, it’s clear that his crackdown on immigration, as well as his blaming of undocumented migrants for societal problems, has not stopped. “This is the worst president, possibly in American history, on immigration,” Charles Kuck said. Kuck is the former president of the American Immigration Lawyers Association as well as the founding partner of the law firm Kuck|Baxter Immigration, and has served as the adjunct professor of law at Emory University since 2013. He spoke about the shock of President Trump’s first election, and how he’s returned much more prepared for his second term, proving more and more that his attack on immigration will not stop at those deemed “dangerous”: “This idea that [Trump and his cabinet] were just going to get rid of criminals or gang members, that’s a lie. That’s a lie because we’re seeing an all-out attack on every aspect of the immigration system, including the immigration system that touches and is controlled by the Constitution of the United States,” Kuck emphasized.

And he’s right- on his very first day back in office, President Trump signed an executive order eliminating the 14th Amendment right to birthright citizenship (though blocked by federal judges). He’s issued several immigration policy rollbacks, even eliminating the task force dedicated to reuniting migrant families (put in place by Executive Order 14011), and he indefinitely suspended refugee resettlement through the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program.

On January 22nd, Trump declared a national emergency at the Southern border, allowing the reserves and National Guard to escalate immigration enforcement, and enabling the reallocation of Department of Defense funds to further border wall construction. He has also described migration across the southern border as an invasion, and has spoken about utilizing the Alien Enemies Act of 1798, which allows the president to deport individuals from countries considered “enemy nations,” in order to execute mass deportations. Kuck spoke about Trump’s recent decision to deport 238 Venezuelans accused of gang membership to El Salvador’s maximum security prison, disobeying a federal judge’s order. The justification provided for this deportation, with many of the deportees having no convictions or prior due process, was the Alien Enemies Act. “It’s unclear to me what constitutional or legal authority the President has to send people who have no immigration issues, no convictions, no findings, to a third country prison, or what authority has to pay for it,” he stated.

The legal immigration process has also been slowed down tremendously on a bureaucratic level: during Trump’s first presidential term, the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) reached some of its lowest processing times and staffing in relation to its workload, and the organization still hasn’t recovered. “You make visas harder, you make green card processing longer, and more frustrating, and more difficult. They can’t change the law, only Congress can change the law, but they can slowly implement the law,” Kuck explained. “The day Biden left, naturalizations were taking four to six months. Now they’re taking 24… Green cards for marriages [which] took four to six months, are now taking 25 to 48 months. We’re seeing visas denied like we’ve never seen before, from abroad, people coming to study, people coming to work. So across the entire spectrum of immigration, we see the attack… when you attack immigrants, that’s just the first level…This is the first step in a totalitarian movement in the United States.”

Georgia has a large and impactful migrant community: a 2023 data report from the American Immigration Council found that the state has about 1,278,200 immigrant residents, 409,500 of whom are undocumented (about 32 percent). The Council reported that in 2023, Georgia immigrant households paid 5.5 billion dollars in state and local taxes, paid 10.3 billion in federal taxes, and made up 15.3 percent of Georgia’s labor force. Georgia’s undocumented immigrants alone paid 2.7 billion dollars in taxes and had a spending power of 9.5 billion dollars, proving that migrants, both undocumented and with legal status, make indisputable contributions to the country’s economy, in addition to enriching communities with diverse perspectives and cultural contributions. One monumental organization working to support its migrant neighbors and protect migrants’ rights is the Georgia Latino Alliance for Human Rights, also known as GLAHR, whose mission is to empower, educate, and mobilize people in the state of Georgia, equipping Latinx people to advocate for themselves and their communities and improve their living conditions. As a result of the anti-immigrant sentiment Trump fueled in 2016, GLAHR launched the campaign “ICE FREE ZONE”, which aimed to inform community members about their constitutional rights in case of interactions with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). I spoke with a GLAHR community organizer, who would like to remain anonymous: “We saw the DHS (Department of Homeland Security) felt empowered, racist sheriffs felt empowered, to question people about their status,” they shared. “They started doing a lot more racial profiling, stopping people for no reason because they knew that the community was vulnerable.”

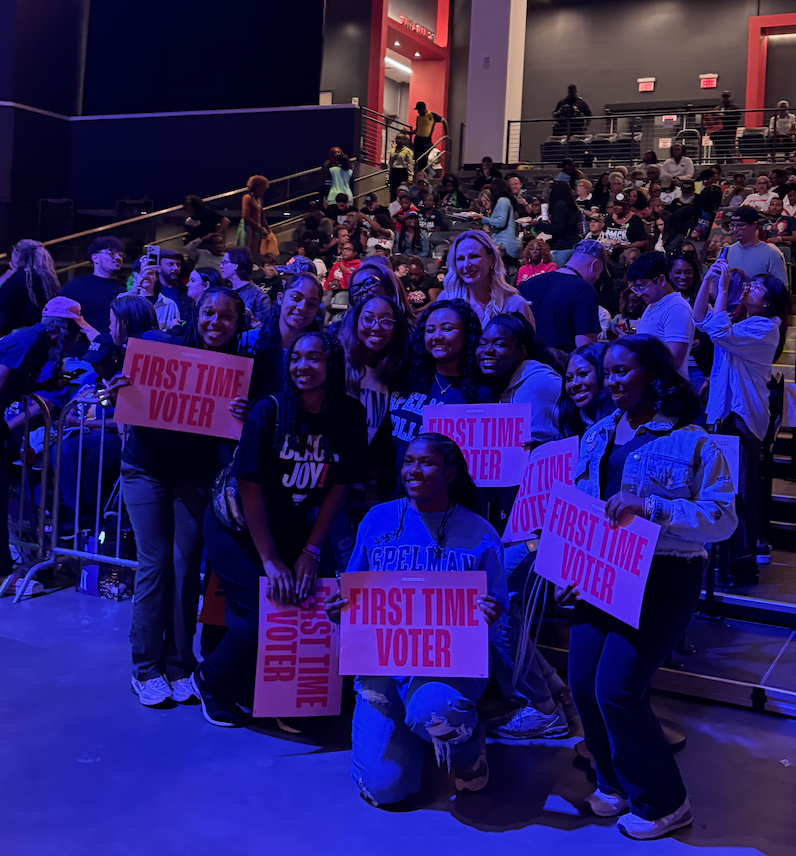

In the years that followed, GLAHR focused on civil engagement and informing Latinos about the election process, prioritizing using the vote as a political defense strategy and making sure community members were informed on candidates’ immigration stances. In the wake of a second Trump Administration, their strategy has slightly shifted, putting much more emphasis on protecting community members at risk: GLAHR relaunched its “ICE Chasers” initiative, a rapid response surveillance team that looks out for ICE in Georgia neighborhoods. This initiative is open to any volunteers willing to undergo training– the GLAHR has trained close to 200 chasers and reached more than 2,000 community members. The GLAHR also has a hotline number people can call for guidance on navigating the immigration process: “In the past four years, it wasn’t that active…now… constantly call after call,” the GLAHR organizer shared. “There’s barely any breaks. So it’s changed. The energy has changed. And we’re using a lot more resources to inform community members and be a response to the community.”

In Georgia, a historically red state, conservative sentiment surrounding immigration is not new. Verifying legal immigration status became a requirement for obtaining a driver’s license in 2008 (Senate Bill 488), meaning that many undocumented migrants who have to drive to work have to risk arrest and deportation. This past February, the state senate passed Senate Bill 21, which would “waive sovereign and governmental immunities for local governments and their officials and employees for a violation of the prohibition on immigration sanctuary policies”– sanctuary cities and counties have been illegal in Georgia since 2009.

Prior to the 2024 presidential election, the case of Laken Riley, a 22-year-old nursing student who was killed by an undocumented Venezuelan migrant in Athens, Georgia, sparked an even greater outcry against illegal immigration by MAGA supporters and other conservatives within Georgia and beyond. On January 20th, 2025, President Trump signed his first piece of legislation, the Laken Riley Act, into federal law, mandating the detention of any undocumented migrant who “has been charged with, arrested for, convicted of, or admits to having committed acts that constitute the essential elements of burglary, theft, larceny, or shoplifting”. Many immigration advocates worry about this law’s ramifications and the power it has to further profile and criminalize undocumented people, particularly Latinx migrants and other migrants of color, especially considering the law doesn’t even require a conviction, but merely an arrest. “It’s not about ICE being on the streets as much in this moment, but it’s [about] how law enforcement [is] criminalizing us,” the GLAHR organizer explained. “Every time we have an interaction with the criminal system, that can lead to a deportation… it changes the game a lot more.”

GLAHR has prioritized raising awareness about the ICE 287(g) program, which enables local law enforcement to enter agreements with the Department of Homeland Security and collaborate in order to conduct immigration enforcement. The “Task Force” Model, which allows ICE to train and supervise local officers to enforce immigration laws during routine policing, was eliminated in 2012 after a Department of Justice investigation uncovered severe racial profiling and discrimination against Latinx people in Arizona. Many migrants have been deported because of 287(g) before even having a chance to fight their case, a clear violation of due process— yet, the Trump Administration has decided to revive and expand it.

In 2021, due to the work of voters and organizers, Cobb County and Gwinnett County– the two Georgia counties with the highest Hispanic and Latinx populations– elected new sheriffs who ended participation in the 287(g) program. However, last year, Georgia passed House Bill 1105, also known as the “Georgia Criminal Alien Track and Report Act of 2024,” requiring all Georgia counties to apply for the program. Fulton County has not yet applied to the 287(g) program. However, part of HB 1105 requires all jails to honor ICE detainers’ requests to pick up migrants, which was optional before the bill’s passage. This means that regardless of the county’s enrollment, ICE can still intervene. Last month, the office of Georgia Governor Brian P. Kemp announced that at the governor’s direction, the Department of Public Safety Commissioner Billy Hitchens requested that ICE “train all 1,100 sworn officers under his command through the 287(g) Program to better assist in identifying and apprehending illegal aliens who pose a risk to public safety in the state.”

Despite the determination to crack down on immigration nationwide, many are eager to fight back. The GLAHR activist emphasized the need for people to organize and support their communities, whether that’s joining a neighborhood ICE Watch or working with your local church to provide shelter or a food pantry for those in need. The organizer also spoke about students pressuring their schools to protect students at risk, as ICE has historically avoided “sensitive areas” such as schools, hospitals, and churches, but Trump’s administration has rescinded these protections: “If your school hasn’t made a statement or passed protocols internally, say, ‘Hey, how are you going to protect our vulnerable students in the institution?’” they suggested. “Or when you go to a school board meeting…pressure them to make statements, you know, pass protocols on how they’ll deny entry to ICE [if] they don’t have proper documentation.”

Those who would like to get involved can support by sharing “Know Your Rights” information in person or via social media, and, if able, can start or participate in neighborhood watch programs like that of the GLAHR in their own communities. If you are interested in learning more about the GLAHR’s work, you can follow the GLAHR on Instagram (@glahr.ga) and plug into similar advocacy organizations committed to migrant safety and the many issue areas that intersect, such as Project South (@projectsouthatl) and the Weelaunee Coalition (@saveweelaunee).