The visionary behind “Fruitvale Station”, “Creed” and “Black Panther”, Ryan Coogler makes his long-awaited horror debut with “Sinners”—a genre-defying film that premiered on April 18 in theaters and IMAX. B

orn in Oakland, California, and earning a Master of Fine Arts from the University of Southern California, Coogler has spent over a decade crafting films that establish him as a storyteller deeply attuned to the social and cultural issues often overlooked by mainstream cinema. With a sharp focus on the racial dynamics of this country and a commitment to uplifting marginalized voices, Coogler conjures fictional worlds that hold space for Black joy, pain, understanding and imagination.

With “Sinners”, Coogler harnesses the horror genre not to escape reality, but to reimagine it—transforming the lived Black experience into a chilling allegory. Through the lens of ancestral memory, systemic violence, and the fragile act of building community under siege, “Sinners” becomes a spectral meditation on the enduring journey African Americans have undertaken since their forced separation from the motherland. The film does not simply scare—it haunts, echoing the traumas that history buries but never erases.

Coogler invites us not only to witness horror but to feel its truth.

“I have loved the genre of horror since I can remember,” Coogler said. “’Sinners’ is my love letter to all the things I love about going to the movies—especially watching with a crowd of people you don’t know.”

Michael B. Jordan reunites with longtime collaborator Ryan Coogler for their fifth project together, this time taking on the dual role of twin brothers Smoke and Stack—characters Jordan describes as the most adventurous role he has played so far. The ensemble cast mirrors the thematic depth Coogler so masterfully weaves throughout the film, featuring Hailee Steinfeld, Miles Caton, Jack O’Connell, Wunmi Mosaku, Jayme Lawson, Omar Miller and Delroy Lindo. Each actor brings not only emotional precision but a profound understanding of the cultural histories their characters represent, spanning Black American, Chinese American, Native American and Irish American communities. In “Sinners”, the performances transcend the conventional bounds of genre, positioning the film within the broader conversation about horror as a tool for advocating marginalized voices in the face of systemic oppression. Following in the footsteps of Jordan Peele’s “Get Out and Us”, “Sinners” adds its voice to the growing body of work that uses horror to challenge white supremacy, becoming an intellectually layered reflection on race, lineage and the complexities of American identity.

Set against the backdrop of the Mississippi Delta in 1932, “Sinners” follows Smoke and Stack, two Black WWI veterans who return home with a truck full of liquor and a dream to build a juke joint—a sanctuary for Black freedom, music and joy. But the promise of rebirth is quickly overshadowed by an ancient evil. Vampires, led by Remmick, a supernatural Irish immigrant with designs on commodifying Black culture, descend upon the Delta. These vampires do not merely seek blood—they hunger for identity, agency,and the cultural richness that the juke joint represents.

In “Sinners”, Coogler blends horror with historical allegory, using vampires to interrogate cultural appropriation and racial exploitation. Through the lens of music, he honors the resilience of African American communities, transforming a genre film into a powerful critique of American history.

“The film is genre-fluid. Yes, vampires are an element, but I’m dealing with archetypes… not just the vampire, but the supernaturally gifted musician,” Coogler said.

Sinners” is an introspection on the violence of assimilation, the theft of Black artistry, and the unyielding spirit of communities who refuse to disappear, even in the face of supernatural and systemic forces.

“Sinners” is grounded in the 1930s, amid the depths of the Great Depression and the oppressive grip of Jim Crow. Black sharecroppers, trapped in cycles of debt, were impoverished, disenfranchised and terrorized by the constant threat of racial violence, with Mississippi having one of the highest lynching rates in the nation. The landscape was a brutal one, where cotton prices had collapsed, leaving many Black farmers destitute. Living in shacks with little access to education or protection, they were victims of a system that denied them voting rights, fair trials and basic humanity under the rigid laws of segregation.

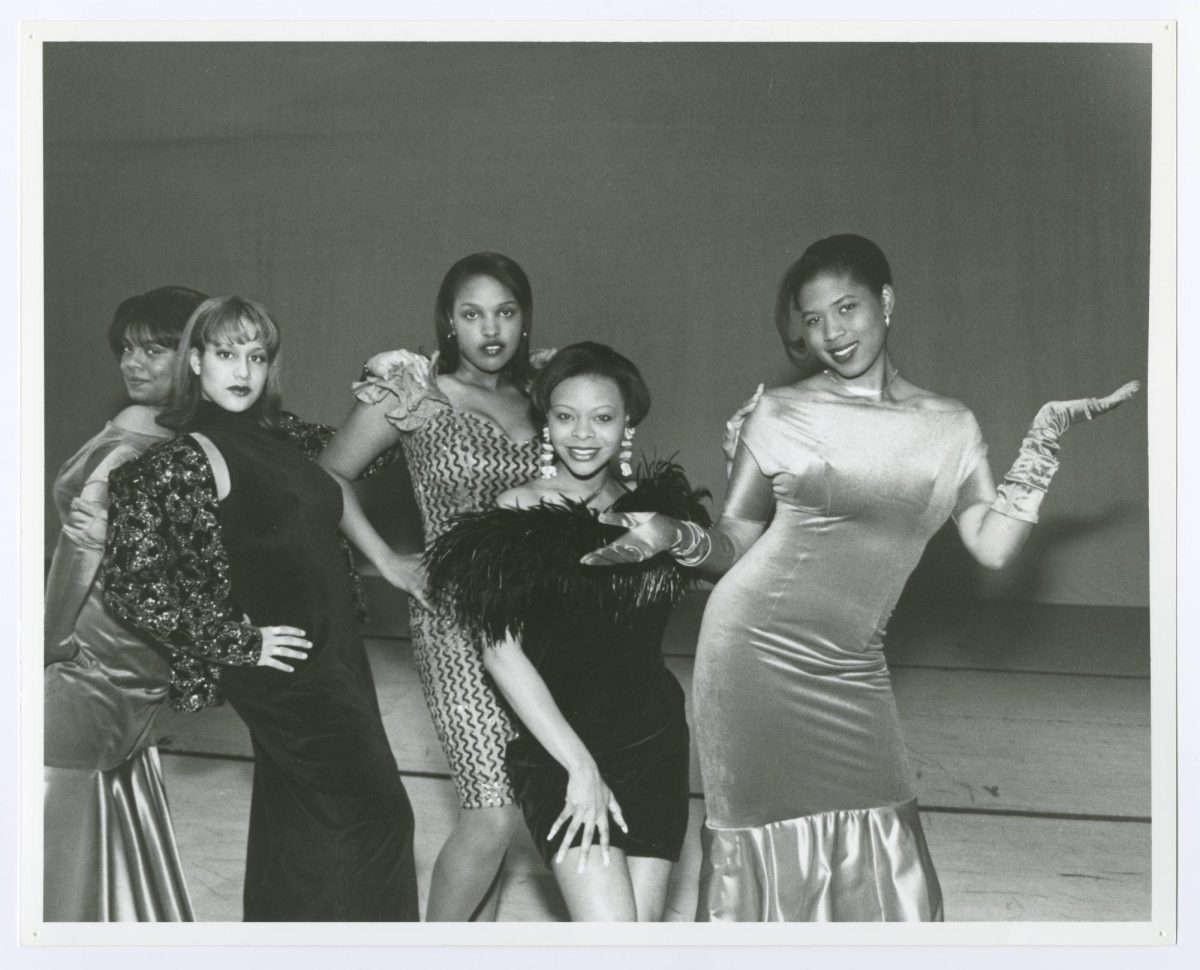

Yet, in the midst of this harrowing reality, the Delta Blues flourished. Coogler describes the Delta as “a place of trauma and transcendence,” where artists like Robert Johnson, Son House, and Charley Patton transformed suffering into sound. The music that emerged was not just a soundtrack but a spiritual language, a form of resistance against the dehumanizing conditions. The juke joint, central to this musical tradition, became more than just a place for revelry; it was a community center, shaped by Black southern culture. For Black people in the Delta, these spaces provided a rare glimpse of autonomy and an escape from the terror of daily life.

To capture this complex environment, Coogler and his team, including production designer Hannah Beachler and cinematographer Autumn Durald Arkapaw, created a world in vivid color, refusing to mute the vibrancy of the era. “You don’t see many movies set in the ’30s South using saturated color,” Beachler remarked, underscoring Coogler’s intention to bring a contemporary feel to “Sinners”. The rich visual texture parallels the emotional intensity of the time: it was a period of deep hardship, but also one of incredible artistic flourishing. This contradictory landscape, steeped in racial violence and economic collapse, gave birth to a genre of music that would go on to change the world. The film’s depiction of the juke joint honors that legacy, showing it as a site of spiritual and cultural resistance, where Black musicians, in the face of terror, could create beauty and communion.

In “Sinners”, music is both a form of resistance and a bridge to ancestral voices. Sammie, a 19-year-old blues guitarist portrayed by Miles Caton, expresses his inner turmoil and aspirations through his haunting performance of “I Lied to You.” For Sammie, his guitar is far more than an instrument—it is his escape, his safety, and his soul. As Caton notes, “That guitar is everything to Sammie.” His live performance immerses the audience in a soundscape that resonates with both historical weight and spiritual depth, echoing the traditions of the Delta Blues while capturing a timeless, ethereal quality.

The juke joint, where Sammie’s music comes to life, for characters like Smoke and Stack, embodies self-determination, a space “for us, by us,” in a world where Black existence is constantly under attack. This sacred space is where joy, survival and community converge, a testament to the resilience of Black culture and identity.

Spirituality is equally integral to the film. Annie, played by Wunmi Mosaku, is a Hoodoo practitioner and herbalist.

“She’s Smoke’s protection, his mother, his lover, and his priestess,” Mosaku said.

Annie’s love and magic are deeply rooted in survival—about transcending fear and embracing the strength of Black heritage. Her rituals, drawn from Yoruba and Southern folk traditions, offer a potent form of spiritual resistance, grounding the film’s supernatural elements in something ancient and authentic to West African culture.

Family and community further strengthen the emotional core of “Sinners”. Smoke and Stack’s juke joint is not just a place of entertainment but a symbol of legacy, self-reliance and the power of shared history. The relationships they build—romantic, familial and spiritual—are the foundation of the film. As Jordan reflects, “It’s about legacy and what we build for ourselves, together.” These bonds create a space where survival, love and creativity can thrive, defying the violence and hardship that surrounds them.

In “Sinners”, the antagonists are vampires—beyond the traditional seductive prototype cinema has seen before. Led by Remmick, played by Jack O’Connell, they represent colonizers in disguise. Remmick is both charming and deeply menacing, a centuries-old vampire with an Irish accent who preys on communities like Clarksdale to maintain his power.

“He’s trying to kill them, sure—but in doing so, he promises them eternal life. That’s the contradiction,” O’Connell said.

This metaphorical vampirism represents whiteness as cultural parasitism—seeking to commodify Black art, exploit Black lives, and appropriate what does not belong to them. Remmick believes he’s offering a gift by offering “eternal life,” yet he’s stealing their souls in the process.

Coogler’s choice to make Remmick Irish is not incidental. Traditionally, vampires originate in Eastern Central Europe, particularly Transylvania, but Remmick’s Irish heritage offers an additional layer to his motivations. As an immigrant victim of colonization, he claims to understand what it’s like to have one’s land and culture stolen. He recalls how white Christians took his father’s land before Ireland was fully converted to Christianity—a loss he still feels deeply. Remmick believes that by colonizing Black culture, he can regain the power and joy stripped from him and his people. In a chilling conversation at the juke joint, he warns Smoke and Stack that the Ku Klux Klan is coming to seize the property they believe belongs to them. Remmick sees Black culture as a new outlet, a new source of power to replace what was taken from him.

This dynamic serves as a biting commentary on the broader history of colonization in America. Coogler uses Remmick’s character to illustrate how different groups, even those who have experienced colonization or cultural erasure themselves, often find a path to power by exploiting Black people. Even as Remmick mourns his lost heritage, he turns to Black culture to regain what was taken from him—at the expense of Black lives.

“Sinners” doesn’t limit itself to a Black-white racial binary; it also weaves in the stories of other marginalized groups, such as Grace and Bo Chow, Chinese American grocers played by Li Jun Li and Yao. This inclusion reflects a little-known yet significant aspect of Southern history.

“There were about 750 Chinese Americans living in Mississippi during that time,” Li said. “They served both Black and white communities while existing in their own complicated social space.”

The Chows’ grocery store acts as a site of quiet resistance, where cultural negotiation unfolds in their daily interactions. Despite being culturally embedded in the community, they are still seen as outsiders, caught between Black and white worlds in ways that add depth to the racial narrative of the film.

The film also evokes Native American culture, through characters and visual motifs that call back to Indigenous storytelling traditions. Coogler’s use of natural imagery—swampland, forests and firelight—reminds viewers of a longer history of colonization that continues to shape the land and its people. These references create a world where colonization is not just a distant past but a living, enduring wound, deeply embedded in the very landscape of the film.

The intersectional struggles represented by Grace, Bo Chow and the film’s evocation of Native American presence form a nuanced tapestry of resistance and survival. In a pivotal moment, Grace, in her desperation to protect her family after the vampires murder her husband and threaten her daughter, invites the vampires into the juke joint. While this decision is motivated by personal grief, it also reflects a painful sacrifice of the Black community’s well-being and culture for her own survival. Despite the support and camaraderie extended by the Black community, Grace chooses to protect her family at the cost of others, symbolizing how marginalized groups often turn on each other in the face of survival.

This moment underscores a broader commentary about American society, where various marginalized communities often find comfort and solace at the expense of Black people. Throughout history, Black culture, joy and well-being have been sacrificed for the benefit of others, a recurring pattern in which Black people are always the ones left to bear the cost of others’ gains. The film’s portrayal of Grace’s sacrifice illustrates this painful reality, highlighting the ways in which Black individuals have always been the sacrificial foundation upon which others build their own lives and futures.

At its core, “Sinners” poses crucial questions: What happens when people try to create something sacred in a world that seeks to erase them? And how do they fight to protect it? These themes go beyond the scares, transforming the film into something that’s not just about survival but about resistance, spirituality and the ongoing fight for cultural preservation.

By intertwining African American, Chinese American and Native American histories with the metaphor of white parasitic vampirism, “Sinners” becomes a kaleidoscope of American oppression and endurance. Coogler’s approach recalls his love for horror films that would still resonate even without the supernatural elements.

“My favorite horror films, you could take the supernatural element out and they’d still work. But that element heightens it,” Coogler said.

“Sinners”, although infused with supernatural elements, is a reality in this country’s historical makeup. The blend of musical elements, spiritual practices originating from West African culture, and even the Americanized understanding of southern Christianity in Black communities are all topics Coogler explores, criticizes and pays homage to in his film. It doesn’t just show what haunts us—it reminds us who we are, where we come from, and how we continue to fight against forces that seek to diminish us. The film’s legacy is one of survival, remembrance, and the enduring strength of community and culture.